Scholarly Review of the Date of the Acts of the Apostles

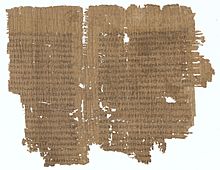

Papyrus manuscript of function of the Acts of the Apostles (Papyrus 8, quaternary century AD)

The historical reliability of the Acts of the Apostles, the principal historical source for the Churchly Historic period, is of interest for biblical scholars and historians of Early on Christianity as part of the argue over the historicity of the Bible.

Archaeological inscriptions and other independent sources bear witness that Acts contains some accurate details of 1st century social club with regard to the titles of officials, administrative divisions, town assemblies, and rules of the Second Temple in Jerusalem. Nonetheless, the historicity of the depiction of Paul the Campaigner in Acts is contested. Acts describes Paul differently from how Paul describes himself, both factually and theologically.[one] Acts differs with Paul'south letters on important issues, such as the Police, Paul's own apostleship, and his relation to the Jerusalem church.[1] Scholars generally adopt Paul'southward account over that in Acts.[2] : 316 [3] : 10

Composition [edit]

Narrative [edit]

Luke–Acts is a two-office historical account traditionally ascribed to Luke, who was believed to be a follower of Paul. The author of Luke–Acts noted that there were many accounts in circulation at the time of his writing, proverb that these were eye-witness testimonies. He stated that he had investigated "everything from the showtime" and was editing the material into one account from the birth of Jesus to his own time. Like other historians of his time,[4] [five] [6] [7] he defined his actions by stating that the reader can rely on the "certainty" of the facts given. However, most scholars empathise Luke–Acts to be in the tradition of Greek historiography.[8] [nine] [10]

Use of sources [edit]

It has been claimed[ by whom? ] that the author of Acts used the writings of Josephus (specifically "Antiquities of the Jews") as a historical source.[eleven] [12] The majority of scholars reject both this claim and the claim that Josephus borrowed from Acts,[xiii] [14] [15] arguing instead that Luke and Josephus drew on mutual traditions and historical sources.[16] [17] [xviii] [19] [20] [21]

Several scholars[ who? ] have criticised the author's use of his source materials. For example, Richard Heard has written that, "in his narrative in the early part of Acts he seems to be stringing together, as best he may, a number of different stories and narratives, some of which appear, past the time they reached him, to have been seriously distorted in the telling."[22] [ folio needed ]

Textual traditions [edit]

Similar most New Attestation books, in that location are differences between the primeval surviving manuscripts of Acts. In the instance of Acts, all the same, the differences between the surviving manuscripts are more substantial than near. Arguably the two earliest versions of manuscripts are the Western text-blazon (as represented past the Codex Bezae) and the Alexandrian text-type (as represented by the Codex Vaticanus and the Codex Sinaiticus which was not seen in Europe until 1859). The version of Acts preserved in the Western manuscripts contains about 6.2-8.5%[23] more content than the Alexandrian version of Acts (depending on the definition of a variant).[3] : 5–6

Modern scholars consider that the shorter Alexandrian text is closer to the original, and the longer Western text is the effect of later insertion of boosted textile into the text.[iii] : 5–half dozen

A tertiary class of manuscripts, known as the Byzantine text-blazon, is often considered to have developed after the Western and Alexandrian types. While differing from both of the other types, the Byzantine type has more similarity to the Alexandrian than to the Western type. The extant manuscripts of this type engagement from the fifth century or subsequently; however, papyrus fragments show that this text-type may date as early equally the Alexandrian or Western text-types.[24] : 45–48 The Byzantine text-blazon served as the basis for the 16th century Textus Receptus, produced by Erasmus, the first Greek-linguistic communication printed edition of the New Testament. The Textus Receptus, in plow, served every bit the basis for the New Testament in the English-language King James Bible. Today, the Byzantine text-type is the subject of renewed involvement as the possible original grade of the text from which the Western and Alexandrian text-types were derived.[25] [ page needed ]

Historicity [edit]

The debate on the historicity of Acts became almost violent between 1895 and 1915.[26] Ferdinand Christian Baur viewed it as unreliable, and mostly an effort to reconcile gentile and Jewish forms of Christianity.[three] : x Adolf von Harnack in particular was known for being very critical of the accuracy of Acts, though his allegations of its inaccuracies have been described as "exaggerated hypercriticism" by some.[27] Leading scholar and archeologist of the fourth dimension menses, William Mitchell Ramsay, considered Acts to be remarkably reliable as a historical document.[28] Attitudes towards the historicity of Acts have ranged widely across scholarship in unlike countries.[29]

According to Heidi J. Hornik and Mikeal C. Parsons, "Acts must be carefully sifted and mined for historical information."[3] : ten

Passages consistent with the historical groundwork [edit]

Acts contains some accurate details of 1st century order, specifically with regard to titles of officials, authoritative divisions, town assemblies, and rules of the Jewish temple in Jerusalem,[thirty] including:

- Inscriptions confirm that the metropolis regime in Thessalonica in the 1st century were called politarchs (Acts 17:half dozen–8)

- According to inscriptions, grammateus is the correct championship for the principal magistrate in Ephesus (Acts 19:35)

- Marcus Antonius Felix and Porcius Festus are correctly called procurators of Judea

- The passing remark of the expulsion of the Jews from Rome by Claudius (Acts xviii:ii) is independently attested by Suetonius in Claudius 25 from The Twelve Caesars, Cassius Dio in Roman History and fifth-century Christian author Paulus Orosius in his History Against the Pagans.[31] [32]

- Acts correctly refers to Cornelius equally centurion and to Claudius Lysias as a tribune (Acts 21:31 and Acts 23:26)

- The title proconsul (anthypathos) is correctly used for the governors of the two senatorial provinces named in Acts (Acts 13:7–8 and Acts 18:12)

- Lucius Junius Gallio Annaeanus's tenure equally proconsul of Achaea is confirmed by the Delphi Inscription (Acts 18:12-17)

- Inscriptions speak virtually the prohibition against the Gentiles in the inner areas of the Temple (equally in Acts 21:27–36); come across also Court of the Gentiles

- The function of town assemblies in the performance of a metropolis's business is described accurately in Acts 19:29–41

- Roman soldiers were permanently stationed in the tower of Antonia with the responsibility of watching for and suppressing whatsoever disturbances at the festivals of the Jews; to reach the affected area they would accept to come down a flight of steps into temple precincts, as noted by Acts 21:31–37

Charles H. Talbert concludes that the historical inaccuracies within Acts "are few and insignificant compared to the overwhelming congruence of Acts and its time [until Advertizing 64] and place [Palestine and the wider Roman Empire]".[30] Talbert cautions still that "an exact description of the milieu does not show the historicity of the event narrated".[33]

Whilst treating its description of the history of the early church skeptically, disquisitional scholars such as Gerd Lüdemann, Alexander Wedderburn, Hans Conzelmann, and Martin Hengel still view Acts as containing valuable historically accurate accounts of the earliest Christians.

Lüdemann acknowledges the historicity of Christ's post-resurrection appearances,[34] the names of the early disciples,[35] women disciples,[36] and Judas Iscariot.[37] Wedderburn says the disciples indisputably believed Christ was truly raised.[38] Conzelmann dismisses an declared contradiction between Acts 13:31 and Acts 1:iii.[39] Hengel believes Acts was written early[40] past Luke as a partial eyewitness,[41] praising Luke'south knowledge of Palestine,[42] and of Jewish community in Acts 1:12.[43] With regard to Acts ane:15–26, Lüdemann is skeptical with regard to the appointment of Matthias, but non with regard to his historical existence.[44] Wedderburn rejects the theory that denies the historicity of the disciples,[45] [46] Conzelmann considers the upper room coming together a historical outcome Luke knew from tradition,[47] and Hengel considers 'the Field of Claret' to be an accurate historical name.[48]

Concerning Acts 2, Lüdemann considers the Pentecost gathering as very possible,[49] and the apostolic instruction to exist historically credible.[50] Wedderburn acknowledges the possibility of a 'mass ecstatic experience',[51] and notes it is hard to explain why early Christians later on adopted this Jewish festival if there had not been an original Pentecost event as described in Acts.[52] He also holds the description of the early on customs in Acts 2 to be reliable.[53] [54]

Lüdemann views Acts iii:1–4:31 as historical.[55] Wedderburn notes what he sees as features of an arcadian description,[56] but notwithstanding cautions against dismissing the record every bit unhistorical.[57] Hengel too insists that Luke described 18-carat historical events, fifty-fifty if he has idealized them.[58] [59]

Wedderburn maintains the historicity of communal ownership among the early followers of Christ (Acts iv:32–37).[60] Conzelmann, though sceptical, believes Luke took his account of Acts half dozen:ane–15 from a written record;[61] more than positively, Wedderburn defends the historicity of the account against scepticism.[62] Lüdemann considers the account to have a historical basis.[63]

Passages of disputed historical accuracy [edit]

Acts 2:41 and iv:4 – Peter's addresses [edit]

Acts iv:4 speaks of Peter addressing an audition, resulting in the number of Christian converts ascent to v,000 people. A Professor of the New Attestation Robert M. Grant says "Luke evidently regarded himself as a historian, only many questions can be raised in regard to the reliability of his history […] His 'statistics' are impossible; Peter could not have addressed iii thousand hearers [e.thousand. in Acts 2:41] without a microphone,[ citation needed ] and since the population of Jerusalem was about 25–thirty,000, Christians cannot take numbered v thousand [e.g. Acts 4:4]."[64] However, as Professor I. Howard Marshall shows, the believers could take possibly come up from other countries (see Acts 2: 9-x). In regards to being heard, contempo history suggests that a crowd of thousands can exist addressed, see for example Benjamin Franklin's account about George Whitefield. [65]

Acts 5:33–39: Theudas [edit]

Acts 5:33–39 gives an business relationship of speech by the 1st century Pharisee Gamaliel (d. ~50ad), in which he refers to two beginning century movements. One of these was led by Theudas.[66] After another was led past Judas the Galilean.[67] Josephus placed Judas at the Census of Quirinius of the year 6 and Theudas under the procurator Fadus[68] in 44–46. Assuming Acts refers to the same Theudas as Josephus, ii problems emerge. First, the order of Judas and Theudas is reversed in Acts 5. 2nd, Theudas'due south motion may come later the time when Gamaliel is speaking. It is possible that Theudas in Josephus is not the aforementioned one as in Acts, or that it is Josephus who has his dates dislocated.[69] The tardily 2nd-century author Origen referred to a Theudas agile before the birth of Jesus,[70] although it is possible that this simply draws on the account in Acts.

Acts ten:1: Roman troops in Caesarea [edit]

Acts 10:one speaks of a Roman Centurion called Cornelius belonging to the "Italian regiment" and stationed in Caesarea virtually 37 Ad. Robert M. Grant claims that during the reign of Herod Agrippa, 41–44, no Roman troops were stationed in his territory.[71] Wedderburn[ who? ] as well finds the narrative "historically suspect",[72] and in view of the lack of inscriptional and literary testify corroborating Acts, historian de Blois[ who? ] suggests that the unit either did not exist or was a after unit which the author of Acts projected to an earlier time.[73]

Noting that the 'Italian regiment' is generally identified as cohors II Italica civium Romanorum, a unit of measurement whose presence in Judea is attested no earlier than AD 69,[74] historian E. Mary Smallwood observes that the events described from Acts 9:32 to chapter 11 may non be in chronological social club with the residuum of the chapter but actually take place after Agrippa'south decease in chapter 12, and that the "Italian regiment" may have been introduced to Caesarea as early on every bit Advertizement 44.[75] Wedderburn notes this suggestion of chronological re-arrangement, along with the proffer that Cornelius lived in Caesarea away from his unit.[76] Historians such as Bond,[77] Speidel,[78] and Saddington,[79] meet no difficulty in the record of Acts ten:1.

Acts 15: The Council of Jerusalem [edit]

The description of the 'Churchly Council' in Acts 15, by and large considered the same event described in Galatians 2,[eighty] is considered by some scholars to be contradictory to the Galatians business relationship.[81] The historicity of Luke'due south account has been challenged,[82] [83] [84] and was rejected completely by some scholars in the mid to tardily 20th century.[85] All the same, more than recent scholarship inclines towards treating the Jerusalem Quango and its rulings as a historical event,[86] though this is sometimes expressed with caution.[87]

Acts fifteen:16–eighteen: James' speech communication [edit]

In Acts fifteen:16–eighteen, James, the leader of the Christian Jews in Jerusalem, gives a speech where he quotes scriptures from the Greek Septuagint (Amos ix:11–12). Some believe this is incongruous with the portrait of James as a Jewish leader who would presumably speak Aramaic, not Greek. For case, Richard Pervo notes: "The scriptural citation strongly differs from the MT which has nothing to practice with the inclusion of gentiles. This is the vital element in the commendation and rules out the possibility that the historical James (who would not have cited the LXX) utilized the passage."[88]

A possible explanation is that the Septuagint translation ameliorate made James's betoken about the inclusion of Gentiles as the people of God.[89] Dr. John Barnett stated that "Many of the Jews in Jesus' day used the Septuagint as their Bible".[90] Although Aramaic was a major linguistic communication of the Ancient Near East, by Jesus's day Greek had been the lingua franca of the surface area for 300 years.

Acts 21:38: The sicarii and the Egyptian [edit]

In Acts 21:38, a Roman asks Paul if he was 'the Egyptian' who led a band of 'sicarii' (literally: 'dagger-men') into the desert. In both The Jewish Wars [91] and Antiquities of the Jews,[92] Josephus talks about Jewish nationalist rebels called sicarii directly prior to talking well-nigh The Egyptian leading some followers to the Mount of Olives. Richard Pervo believes that this demonstrates that Luke used Josephus equally a source and mistakenly thought that the sicarii were followers of The Egyptian.[93] [94]

Other sources for early Church history [edit]

2 early sources that mention the origins of Christianity are the Antiquities of the Jews by the Roman-Jewish historian Josephus, and the Church History of Eusebius. Josephus and Luke-Acts are idea to be approximately contemporaneous, around Advertisement xc, and Eusebius wrote some two and a quarter centuries later.

More indirect evidence can be obtained from other New Testament writings, early Christian apocrypha, and non-Christian sources such every bit the correspondence betwixt Pliny and Trajan (112 CE). Even Christian pseudepigrapha sometimes requite potential insights into how early on Christian communities formed and functioned,and the kinds of issues they faced and what sort of behavior they developed, although care must be taken to distinguish fact from fiction.

See also [edit]

- Historical method

- Historical reliability of the Gospels

- Luke-Acts

- Authorship of Luke-Acts

References [edit]

- ^ a b Cain, Seymour; et al. "Biblical literature". Encyclopædia Britannica Online . Retrieved xv November 2018.

- ^ Harris, Stephen (1985). Understanding the Bible: A Reader's Introduction (second ed.). Mayfield Pub. Co. ISBN978-0874846966.

- ^ a b c d e Hornik, Heidi J.; Parsons, Mikeal C. (2017). The Acts of the Apostles through the centuries (1st ed.). John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. ISBN9781118597873.

- ^ Aune, David (1988). The New Testament in Its Literary Surround. James Clarke & Co. pp. 77–. ISBN978-0-227-67910-4.

- ^ Daniel Marguerat (five September 2002). The Beginning Christian Historian: Writing the 'Acts of the Apostles' . Cambridge Academy Printing. pp. 63–. ISBN978-one-139-43630-4.

- ^ Clare Thou. Rothschild (2004). Luke-Acts and the Rhetoric of History: An Investigation of Early Christian Historiography. Mohr Siebeck. pp. 216–. ISBN978-iii-16-148203-8.

- ^ Todd Penner (18 June 2004). In Praise of Christian Origins: Stephen and the Hellenists in Lukan Apologetic Historiography. Bloomsbury Academic. pp. 45–. ISBN978-0-567-02620-0.

- ^ Grant, Robert M., "A Historical Introduction to the New Attestation" (Harper and Row, 1963) "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2010-06-21. Retrieved 2009-11-24 .

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived re-create as title (link) - ^ Phillips, Thomas E. "The Genre of Acts: Moving Toward a Consensus?" Currents in Biblical Enquiry 4 [2006] 365 – 396.

- ^ "Hengel classifies Acts as a "historical monograph," equally authentic as the work of any other ancient historian. Cadbury thinks the author is closest to being a historian, but writes on a pop level. Others compare the author to the ancient historian Thucydides, peculiarly in the matter of composed speeches that strive for verisimilitude. L. Donelson characterizes the author as a cult historian who travels from place to identify gathering traditions, setting down the origin of the sect. Pervo observes that even scholars such as Haenchen who rate the author equally highly unreliable however classify him as a historian.", Setzer, "Jewish responses to early Christians: history and polemics, 30–150 C.Due east." (1994). Fortress Printing.

- ^ 'This theory was maintained past F. C. Burkitt (The Gospel History and its Transmission, 1911, pp. 105–110), following the arguments of Krenkel's Josephus und Lucas (1894).', Guthrie, 'New Attestation Introduction', p. 363 (fourth rev. ed. 1996). Tyndale Press.

- ^ 'Conspicuously Luke makes significant utilize of the LXX in both the gospels and Acts. In addition it is often alleged that he fabricated apply of the writings of Josephus and the letters of Paul. The employ of the Seventy is not debatable, but the influence of Josephus and Paul has been and is subjected to considerable contend.', Tyson, 'Marcion and Luke-Acts: a defining struggle', p. 14 (2006).Academy of California Printing.

- ^ 'Neither position has much of a following today, considering of the significant differences between the two works in their accounts of the same events.', Mason, 'Josephus and the New Testament', p. 185 (1992). Baker Publishing Group.

- ^ 'After examining the texts myself, I must conclude with the majority of scholars that it is impossible to establish the dependence of Luke-Acts on the Antiquitates.', Sterling, 'Historiography and Cocky-Definition: Josephus, Luke-Acts, and Apologetic Historiography', Supplements to Novum Testamentum, pp. 365–366 (1992). Brill.

- ^ 'Almost scholars today deny any dependence one fashion or the other, and we call up this judgment is right.', Heyler, 'Exploring Jewish literature of the 2nd Temple Period: A Guide for New Testament Students', p. 362 (2002). InterVarsity Press.

- ^ 'Sterling concludes that, while it is impossible to institute a literary dependence of Luke-Acts on the writings of Josephus, information technology is reasonable to assert that both authors not only had access to similar historical traditions merely besides shared the same historiographical techniques and perspectives.', Verheyden, 'The Unity of Luke-Acts', p. 678 (1990). Peeters Publishing.

- ^ 'It seems likely that Luke and Josephus wrote independently of one another; for each could certainly accept had access to sources and data, which he then employed according to his own perspectives. A characteristic conglomerate of details, which in part concur, in role reverberate cracking similarity, simply also in part, appear dissimilar and to stalk from different provenances, accords with this analysis.', Schreckenberg & Schubert, 'Jewish Historiography and Iconography in Early on and Medieval Christian Literature', Compendia Rerum Iudicarum Ad Novum Testamentum, volume 2, p. 51 (1992). Uitgeverij Van Gorcum.

- ^ 'The human relationship between Luke and Josephus has produced an abundant literature, which has attempted to show the literary dependence of 1 on the other. I practice not believe that any such dependence tin be proved.', Marguerat, 'The Start Christian Historian: writing the "Acts of the Apostles"', p. 79 (2002). Cambridge Academy Press.

- ^ 'Arguments for the dependence of passages in Acts on Josephus (especially the reference to Theudas in Acts v. 37) are as unconvincing. The fact is, as Schurer has said: "Either Luke had not read Josephus, or he had forgotten all nearly what he had read"', Geldenhuys, 'Commentary on the Gospel of Luke', p. 31 (1950).Tyndale Press.

- ^ 'After examining the texts myself, I must conclude with the bulk of scholars that it is incommunicable to found the dependence of Luke-Acts on the Antiquitates. What is clear is that Luke-Acts and Josephus shared some common traditions nearly the recent history of Palestine.', Sterling, 'Historiography and Self-Definition: Josephus, Luke-Acts, and Apologetic Historiography', Supplements to Novum Testamentum, pp. 365–366 (1992). Brill.

- ^ 'When we consider both the differences and the agreement in many details of the information in the two accounts, [of the death of Herod Agrippa I] it is surely better to suppose the beingness of a mutual source on which Luke and Josephus independently drew.', Klauck & McNeil, 'Magic and Paganism in Early Christianity: the world of the Acts of the Apostles', p. 43 (2003). Continuum International Publishing Group.

- ^ Heard, Richard: An Introduction to the New Testament Chapter 13: The Acts of the Apostles, Harper & Brothers, 1950

- ^ Nicklas, Tobias (Jan 1, 2003). The Book of Acts as Church History. New York: Dice Deutsche Bibliothek. pp. 32–33. ISBN978-3-eleven-017717-six.

- ^ Colwell, Ernest C. (1969). Studies in methodology in textual criticism of the New Attestation. New Testament Tools, Studies and Documents, Book: 9. Brill. ISBN9789004015555.

- ^ Robinson, Maurice A; Pierpont, William G. (2005). The New Testament in the original Greek : Byzantine textform (1st ed.). Chilton Book Pub. ISBN0-7598-0077-iv.

- ^ "In the menstruum approximately 1895–1915 in that location was a far reaching, multi-facted, high-level debate over the historicity of Acts.", Hemer & Gempf, "The Volume of Acts in the Setting of Hellenistic History", p.iii (1990). Mohr Siebeck.

- ^ "It is difficult to deport Harnack hither of an exaggerated hypercriticism. He constructed a lengthy list of inaccuracies (Harnack, Acts pp. 203–31), but most of the entries are bizarrely trivial:", Hemer & Gempf, "The Book of Acts in the Setting of Hellenistic History", p. seven (1990). Mohr Siebeck.

- ^ Ramsay, William (1915). The Begetting of Recent Discovery on the Trustworthiness of the New Testament. London: Hodder and Stoughton. p. 85, 89.

Further study … showed that the volume [of Acts] could comport the about minute scrutiny as an authority for the facts of the Aegean world, and that it was written with such judgment, skill, fine art and perception of truth equally to be a model of historical statement. . . . I ready out to await for truth on the borderland where Greece and Asia meet, and found it [in Acts]. You may press the words of Luke in a caste beyond whatever other historian's and they stand the keenest scrutiny and the hardest handling.

- ^ "British scholarship has been relatively positive about Acts' historicity, from Lightfoot and Ramsay to Westward.L. Knox and Bruce. German scholarship has, for the virtually role, evaluated negatively the historical worth of Acts, from Baur and his school to Dibelius, Conzelmann, and Haenchen. North American scholars bear witness a range of opinion. Mattill and Gasque align with the British approach to Acts. Cadbury and Lake have a moderate line and to some caste sidestep the question of accurate historicity.", Setzer, "Jewish responses to early Christians: history and polemics, 30–150 C.E.", p. 94 (1994). Fortress Press.

- ^ a b Talbert, "Reading Luke-Acts in its Mediterranean Milieu", pp. 198–200 (2003). Brill.

- ^ Rainer Riesner "Pauline Chronology" in Stephen Westerholm The Blackwell Companion to Paul (May 16, 2011) ISBN 1405188448 pp.13-xiv

- ^ Andreas J. Köstenberger, L. Scott Kellum, The Cradle, the Cross, and the Crown: An Introduction to the New Testament (2009) ISBN 978-0-8054-4365-3 p. 110, 400

- ^ Talbert, "Reading Luke-Acts in its Mediterranean Milieu", p. 201 (2003)

- ^ '"There were in fact appearances of the heavenly Jesus in Jerusalem (after those in Galilee)" (ibid., 29–30)"', Lüdemann quoted by Matthews, 'Acts and the History of the Earliest Jerusalem Church building', in Cameron & Miller (eds.), 'Redescribing Christian origins', p. 164 (2004); he attributes the appearances to hallucination.

- ^ '"The names of the disciples of Jesus are for the well-nigh part certainly historical["].', Lüdemann quoted by Matthews, 'Acts and the History of the Earliest Jerusalem Church building', in Cameron & Miller (eds.), 'Redescribing Christian origins', p. 164 (2004)

- ^ '["]The existence of women disciples as members of the earliest Jerusalem customs is also a historical fact" (ibid., 31).', Lüdemann quoted by Matthews, 'Acts and the History of the Earliest Jerusalem Church', in Cameron & Miller (eds.), 'Redescribing Christian origins', p. 164 (2004)

- ^ '"The disciple Iscariot is without doubt a historical person... [who] made a decisive contribution to delivering Jesus into the hands of the Jewish authorities" (ibid., 35–36).', Lüdemann quoted by Matthews, 'Acts and the History of the Earliest Jerusalem Church', in Cameron & Miller (eds.), 'Redescribing Christian origins', p. 165 (2004)

- ^ 'Whatever one believes about the resurrection of Jesus,5 information technology is undeniable that his followers came to believe that he had been raised by God from the dead, that the one who had plainly died an ignominious death, forsaken and even accursed past his God, had subsequently been vindicated past that aforementioned God., ' Wedderburn, 'A History of the First Christians', p. 17 (2004).

- ^ 'According to this verse Jesus seems to appear simply to the apostles (for Luke, the Twelve), while the parallel in 13:31* says he appeared to all who went with him on the journey from Galilee to Jerusalem. The contradiction is not a serious one, notwithstanding, nor is there any real difference between the xl days mentioned in this text and the ἡμέρας πλείους, "many days," of 13:31*.', Conzelmann, Limber (trans.), Epp, & Matthews (eds.), 'Acts of the Apostles: A commentary on the Acts of the Apostles', Hermeneia, p. 5 (1987).

- ^ 'That makes it all the more than hit that Acts says goose egg of Paul the letter-writer. In my view this presupposes a relatively early date for Acts, when there was yet a brilliant memory of Paul the missionary, only the letter-writer was non known in the aforementioned fashion.', Hengel & Schwemer, 'Paul Between Damascus and Antioch: the unknown years', p. 3 (1997).

- ^ 'Contrary to a widespread anti-Lukan scholasticism which is frequently relatively ignorant of ancient historiography, I regard Acts equally a piece of work that was equanimous soon subsequently the Third Gospel past Luke 'the beloved doc' (Col. 4:14), who accompanied Paul on his travels from the journey with the collection to Jerusalem onwards. In other words, equally at least in part an center-witness account for the late period of the apostle, virtually which we no longer have whatever information from the letters, it is a first-hand source.', Hengel & Schwemer, 'Paul Between Damascus and Antioch: the unknown years', p. 7 (1997).

- ^ 'So Luke-Acts looks dorsum on the destruction of Jerusalem, which is still relatively recent, and moreover is admirably well informed about Jewish circumstances in Palestine, in this respect comparable only to its gimmicky Josephus. Every bit Matthew and John attest, that was no longer the case around fifteen–25 years afterwards; one need just compare the historical errors of the old Platonic philosopher Justin from Neapolis in Samaria, who was born around 100 CE.', Hengel & Schwemer, 'Paul Between Damascus and Antioch: the unknown years', pp. 7–viii (1997).

- ^ 'The term 'a sabbath day's journeying', which appears but here in the New Testament, presupposes an amazingly intimate knowledge — for a Greek — of Jewish community.', Hengel, 'Between Jesus and Paul: studies in the earliest history of Christianity', p. 107 (1983).

- ^ '"One is... inclined to claiming the historicity of the election of Matthias... This does non hateful, though, that the Jerusalem Christians Matthias and Joseph were non historical figures" (ibid., 37).', Lüdemann quoted by Matthews, 'Acts and the History of the Earliest Jerusalem Church', in Cameron & Miller (eds.), 'Redescribing Christian origins', p. 166 (2004)

- ^ 'Yet is such a theory not an human activity of agony?21 Is it non in every way simpler to accept that the Twelve existed during Jesus' lifetime and that Judas was one of them?', Wedderburn, 'A History of the First Christians', p. 22 (2004).

- ^ 'The presence of some names in the list is, in view of their relative obscurity, virtually hands explained by their having indeed been members of this group.', Wedderburn, 'A History of the Get-go Christians', p. 22 (2004).

- ^ 'A local tradition well-nigh the coming together identify can yet be detected. The upper room is the place for prayer and conversation (xx:8*; cf. Dan vi:11*), and for seclusion (Mart. Pol. 7.i). The list of names agrees with Luke 6:13–16*.', Conzelmann, Limber (trans.), Epp, & Matthews (eds.), 'Acts of the Apostles: A commentary on the Acts of the Apostles', Hermeneia, pp. 8–9 (1987); he however believes the waiting for the spirit is a fiction by Luke.

- ^ 'The Aramaic designation Akeldamakc for 'field of blood' has been correctly handed downward in Acts one:19; this is a place proper noun which is likewise known by Matthew 27:viii', Hengel, 'The Geography of Palestine in Acts', in Bauckham (ed.), 'The Book of Acts in its Palestinian Setting', p. 47 (1995).

- ^ 'Although doubting that the specification "Pentecost" belongs to the tradition, Lüdemann supposes, on the basis of references to glossolalia in Paul's messages and the ecstatic prophecy of Philip's daughters (Acts 21:9), that "nosotros may certainly regard a happening of the kind described by the tradition backside vv.one–four equally very possible."', Lüdemann quoted by Matthews, 'Acts and the History of the Primeval Jerusalem Church', in Cameron & Miller (eds.), 'Redescribing Christian origins', p. 166 (2004)

- ^ '"The education past the apostles is besides to be accustomed as historical, since in the early period of the Jerusalem customs the apostles had a leading role. And so Paul can speak of those who were apostles before him (in Jerusalem!, Gal. 1.17)" (twoscore.)', Lüdemann quoted past Matthews, 'Acts and the History of the Primeval Jerusalem Church building', in Cameron & Miller (eds.), 'Redescribing Christian origins', p. 166 (2004).

- ^ 'Information technology is also possible that at some indicate of time, though not necessarily on this 24-hour interval, some mass ecstatic experience took identify.', Wedderburn, 'A History of the First Christians', p. 26 (2004).

- ^ 'At any charge per unit, as Weiser and Jervell betoken out,39 it needs to be explained why early Christians adopted Pentecost every bit one of their festivals, assuming that the Acts account was non reason enough.', Wedderburn, 'A History of the First Christians', p. 27 (2004).

- ^ 'Many features of them are too intrinsically likely to be lightly dismissed every bit the invention of the author. Information technology is, for instance, highly probable that the earliest community was taught by the apostles (2:42)—at least by them among others.', Wedderburn, 'A History of the Beginning Christians', p. xxx (2004).

- ^ 'Once more, if communal meals had played an important part in Jesus' ministry building and had indeed served and so as a sit-in of the inclusive nature of God'south kingly dominion, and so information technology is merely to exist expected that such meals would continue to form a prominent function of the life of his followers (Acts 2:42, 46), even if they and their symbolic and theological importance were a theme particularly dear to 'Luke'south' heart.47 It is every bit probable that such meals took place, indeed had to take place, in private houses or in a private business firm (ii:46) and that this community was therefore dependent, every bit the Pauline churches would be at a later on stage, upon the generosity of at least one member or sympathizer who had a house in Jerusalem which could exist placed at the disposal of the group. At the same time it might seem unnecessary to deny another feature of the account in Acts, namely that the starting time followers of Jesus too attended the worship of the Temple (2:46; iii:1; 5:21, 25, 42), even if they also used the opportunity of their visits to the shrine to spread their message among their fellow-worshippers. For without question they would have felt themselves to be withal part of Israel.', Wedderburn, 'A History of the First Christians', p. xxx (2004).

- ^ "Despite what is in other respects the negative result of the historical analysis of the tradition in Acts iii–4:31, the question remains whether Luke'south general knowledge of this period of the primeval community is of historical value. We should probably respond this in the affirmative, because his description of the disharmonize between the earliest customs and the priestly nobility rests on right historical assumptions. For the missionary activity of the primeval community in Jerusalem not long afterwards the crucifixion of Jesus may accept alarmed Sadducean circles... so that they might at least have prompted considerations near action against the Jesus customs.", Lüdemann quoted by Matthews, 'Acts and the History of the Primeval Jerusalem Church', in Cameron & Miller (eds.), 'Redescribing Christian origins', pp. 168–169 (2004).

- ^ 'The presence of such idealizing features does not mean, nonetheless, that these accounts are worthless or offer no data about the earliest Christian community in Jerusalem.46 Many features of them are too intrinsically probable to exist lightly dismissed every bit the invention of the writer.', Wedderburn, 'A History of the Start Christians', p. xxx (2004).

- ^ 'At the same time it might seem unnecessary to deny some other feature of the account in Acts, namely that the first followers of Jesus as well attended the worship of the Temple (2:46; 3:ane; 5:21, 25, 42), even if they also used the opportunity of their visits to the shrine to spread their message among their fellow-worshippers. For without question they would have felt themselves to exist still part of Israel.48 The earliest community was entirely a Jewish one; even if Acts ii:5 reflects an earlier tradition which spoke of an ethnically mixed audience at Pentecost,49 it is articulate that for the author of Acts just Jewish hearers come in question at this stage and on this point he was in all probability correct.', Wedderburn, 'A History of the Offset Christians', p. 30 (2004).

- ^ 'In that location is a historical occasion behind the description of the story of Pentecost in Acts and Peter'south preaching, fifty-fifty if Luke has depicted them with relative freedom.', Hengel & Schwemer, 'Paul Between Damascus and Antioch: the unknown years', p. 28 (1997).

- ^ 'Luke's ideal, stained-drinking glass depiction in Acts two–v thus has a very real background, in which events followed one another rapidly and certainly were much more turbulent than Acts portrays them.', Hengel & Schwemer, 'Paul Between Damascus and Antioch: the unknown years', p. 29 (1997).

- ^ 'Is there any truth, however, in Acts' repeated references to a sharing of goods or is this only an idealizing feature invented by the author? For a start information technology is not clear whether he envisages property existence sold and the gain distributed to the needy (and then in two:45; four:34–5, 37) or whether the property is retained but the use of it is shared with other members of the community (cf. 2:44, 'all things in common'). Yet even this incertitude is near readily intelligible if at least 1 of these variants is traditional; if anything is to be attributed to the writer'south idealizing trend information technology is the motif of 'all things in common', but, as we saw, the mention in 12:12 of the house of Mary, John Mark's female parent, points to a physical example of something not sold, but held in common. If Barnabas possessed a field (4:37), on the other hand, so this is not probable to accept been so immediately useful to the Jerusalem community, particularly if it was in his native Cyprus; yet information technology has been suggested that information technology was near Jerusalem (and may start have been sold when Barnabas was despatched to, or left for, Antioch—Acts 11:22).55 Some would certainly regard the whole picture of this sharing, in whatever form, equally the product of the author'due south imagination, but it is to be noted, not only that what he imagines is not wholly clear, but as well that in that location are contemporary parallels which suggest that such a sharing is by no means unthinkable.', Wedderburn, 'A History of the First Christians', pp. 31–33 (2004).

- ^ 'Backside this business relationship lies a slice of tradition which Luke must have had in written class; note the manner in which the "Hellenists" and "Hebrews" are introduced.', Conzelmann, Limber (trans.), Epp, & Matthews (eds.), 'Acts of the Apostles: A commentary on the Acts of the Apostles', Hermeneia, p. 44 (1987).

- ^ 'A quarrel arose because the widows of the 'Hellenists' were neglected in the daily distribution of help. This is depicted as an internal squabble which had to be settled within the Christian community and that implies that the earliest Christian community already had its own poor-relief organisation. Some take doubted that and therefore regard this account every bit anachronistic.10 Yet information technology is to be noted that it hangs together with the business relationship of the pooling of resources mentioned earlier in Acts: the church had the ways to offering assistance and, indeed, if information technology did not use what was offered to it in some such way, it is difficult to see how it would otherwise take used such funds.',Wedderburn, 'A History of the Start Christians', p. 44 (2004).

- ^ 'The tradition of the presence in Jerusalem of the groups named in v. 9 has a adept bargain to be said for it historically...', Lüdemann quoted by Matthews, 'Acts and the History of the Earliest Jerusalem Church', in Cameron & Miller (eds.), 'Redescribing Christian origins', p. 171 (2004).

- ^ Grant, Robert G., "A Historical Introduction to the New Testament", p. 145 (Harper and Row, 1963)

- ^ Marshall, I. Howard., "Tyndale New Testament Commentaries: Acts", p. 82, and 98-99

- ^ Acts, five:36

- ^ Acts five:37

- ^ Jewish Encyclopedia: Theudas: "Bibliography: Josephus, Ant. xx. 5, § i; Eusebius, Hist. Eccl. II. ii.; Schmidt, in Herzog-Plitt, Real-Encyc. xv. 553–557; Klein, in Schenkel, Bibel-Lexikon, 5. 510–513; Schürer, Gesch. i. 566, and note 6."

- ^ A. J. G. Wedderburn, A History of the Start Christians, Continuum, 2004, p.xiv.

- ^ Contra Celsum 1.57

- ^ Grant, Robert Chiliad., A Historical Introduction to the New Testament, p. 145 (Harper and Row, 1963)

- ^ "The reference to the presence in Caesarea of a centurion of the 'Italian' accomplice is, however, historically doubtable. If a cohors Italica civium Romanorum is meant, i.due east. a cohort of Roman auxiliaries consisting chiefly of Roman citizens from Italy, then such a unit may take been in Syrian arab republic shortly earlier 69 (cf. Hemer, Book, 164), merely was one to be establish in Caesarea in the fourth dimension just earlier Herod Agrippa I'southward death (cf. Haenchen, Acts, 346 n. ii and 360); Schurer, HIstory one, 366 n. 54)?", Wedderburn[ who? ], "A History of the Commencement Christians", p. 217 (2004). Continuum Publishing Group.

- ^ "As for the Italian cohort, Speidel claims that it is a cohors civium Romanorum. Speidel actually identifies a cohors Two Italica c.R. that was in Syria equally early on as AD 63, though it moved to Noricum before the Jewish war. As he argues, this unit of measurement could exist the one called the speire tes kaloumenes Italike in the New Testament's Acts of the Apostles. The unit is not mentioned by Josephus nor is there epigraphical prove for information technology at Caesarea nor anywhere in Judea. It is possible that the unit did not be or was a afterwards Syrian unit displaced to a unlike place and earlier time.", de Blois et al (eds.), "The Impact of the Roman Army (200 B.C. – A.D. 476): Economic, Social, Political, Religious and Cultural Aspects: Proceedings of the Sixth Workshop of the International Network Touch of Empire (Roman Empire, 200 B.C. – A.D. 476), Capri, Italian republic, March 29 – April ii, 2005", p. 412 (2005). Brill.

- ^ "At that place is inscriptional evidence for the presence in Syrian arab republic in A.D. 69 of the auxiliary cohors 2 Italica civium Romanorum (Dessau, ILS 9168); but we have no direct show of the identity of the war machine units in Judaea between A.D. half-dozen and 41. from A.D. 41 to 44, when Agrippa I reigned over Judaea (come across on 12:1), one important corps consisted of troops of Caesarea and Sebaste, Kaisareis kai Sebasthnoi (Jos. Emmet. 19.356, 361, 364f.), who did not take kindly to the command of a Jewish king.", Bruce, "The Acts of the Apostles: The Greek Text with Introduction and Commentary", p. 252 (1990). Eerdmans.

- ^ "Acts 10, 1, speirh Italikh, generally identified with cohors 2 Italica c. R., which was probably in Syria by 69 – Gabba, Iscr. Bibbia 25-6 (=ILS 9168; CIL Xi, 6117); c.f. P.-W., s.five. cohors, 304. Jackson and Lake, Beginnings V, 467-nine, argue that the events of Acts ix, 32-xi are misplaced and belong subsequently Agrippa I's death (ch. xii). If and so, the cohors Italica may have come in with the reconstitution of the province in 44 (beneath, p. 256).", Smallwood, "The Jews Under Roman Rule: From Pompey to Diocletian: a study in political relations" p.147 (2001). Brill.

- ^ "Others engagement the incident either before Herod'southward reign (so Bruce, History, 261, following Acts' sequence) or more probable after information technology, unless 1 supposes that this officeholder had been seconded to Caesarea without the rest of his unit of measurement (cf. also Hengel, 'Geography', 203-four due north. 111).", Wedderburn, "A History of the First Christians", p. 217 (2004). Continuum Publishing Group.

- ^ "One of these infantry cohorts may well have been the cohors 2 Italica civium romanorum voluntariorum referred to in Acts ten; see Hengel, Betwixt, p. 203, n. 111.", Bond, "Pontius Pilate in History and Interpretation", p. 13 (1998). Cambridge University Press.

- ^ "Certainly after Titus' Jewish war the Flavian emperors revamped the Judaean army, and at the same fourth dimension cohors II Italica seems to have been transferred n into Syria, equally were ala and cohors I Sebastenorum of the same provincial regular army, yet for the time of the procurators in that location is no reason to doubt the accuracy of Acts ten.", Speidel, "Roman Army Studies', volume ii, p. 228 (1992). JC Bieben.

- ^ "The Coh. Italica and, possibly as well, the Coh. Augusta were prestigious regiments. Their functioning in Judaea cannot be placed before Advertizing 40 on the evidence available, but it is of course possible that they had been sent there before that, even nether the first prefect after the fall of Archelaus.", Saddington, "Military and Administrative Personnel in the NT", in "Aufstieg und Niedergang der römischen Welt", pp. 2417–2418 (1996). Walter de Gruyter.

- ^ "In spite of the presence of discrepancies between these two accounts, most scholars agree that they do in fact refer to the aforementioned effect.", Paget, "Jewish Christianity", in Horbury, et al., "The Cambridge History of Judaism: The Early on Roman Menses", volume iii, p. 744 (2008). Cambridge Academy Press.

- ^ "Paul's account of the Jerusalem Council in Galatians 2 and the account of it recorded in Acts have been considered by some scholars as being in open contradiction.", Paget, "Jewish Christianity", in Horbury, et al., "The Cambridge History of Judaism: The Early on Roman Menstruum", volume 3, p. 744 (2008). Cambridge University Press.

- ^ "In that location is a very strong case against the historicity of Luke's account of the Churchly Council", Esler, "Community and Gospel in Luke-Acts: The Social and Political Motivations of Lucan Theology", p. 97 (1989). Cambridge University Press.

- ^ "The historicity of Luke's account in Acts fifteen has been questioned on a number of grounds.", Paget, "Jewish Christianity", in Horbury, et al., "The Cambridge History of Judaism: The Early on Roman Period", volume 3, p. 744 (2008). Cambridge University Press.

- ^ "Yet, numerous scholars take challenged the historicity of the Jerusalem Quango equally related by Acts, Paul's presence there in the manner that Luke described, the issue of idol-food being thrust on Paul's Gentile mission, and the historical reliability of Acts in general.", Fotopolous, "Nutrient Offered to Idols in Roman Corinth: a socio-rhetorical reconsideration", pp. 181–182 (2003). Mohr Siebeck.

- ^ "Sahlin rejects the historicity of Acts completely (Der Messias und das Gottesvolk [1945]). Haenchen's view is that the Apostolic Council "is an imaginary structure answering to no historical reality" (The Acts of the Apostles [Engtr 1971], p. 463). Dibelius' view (Studies in the Acts of the Apostles [Engtr 1956], pp. 93–101) is that Luke's treatment was literary-theological and can make no claim to historical worth.", Mounce, "Apostolic Quango", in Bromiley (ed.) "The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia", book 1, p. 200 (rev. ed. 2001). Wm. B. Eerdmans.

- ^ "There is an increasing tendency among scholars toward because the Jerusalem Council equally historical event. An overwhelming bulk identifies the reference to the Jerusalem Council in Acts 15 with Paul's business relationship in Gal. 2.1–10, and this accordance is not merely limited to the historicity of the gathering solitary but extends also to the authenticity of the arguments deriving from the Jerusalem church itself.", Philip, "The Origins of Pauline Pneumatology: the Eschatological Bestowal of the Spirit", Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Attestation 2, Reihe, p. 205 (2005). Mohr Siebeck.

- ^ "The present writer accepts its bones historicity, i.e. that there was an event at Jerusalem concerning the matter of the entry of the Gentiles into the Christian community, simply would exist circumspect about going much further than that. For a robust defence of its historicity, run across Bauckham, "James", and the relevant literature cited there.", Paget, "Jewish Christianity", in Horbury, et al., "The Cambridge History of Judaism: The Early Roman Period", book iii, p. 744 (2008). Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Pervo, Richard I., Acts – a commentary, Fortress Press, Minneapolis, 2009, p. 375-376

- ^ Evans, Craig A., The Bible Knowledge Groundwork Commentary, Cook Communications Ministries, Colorado Springs Colorado, 2004, 102.

- ^ Barnett, John, What Bible did Jesus use?, http://www.biblestudytools.com/bible-study/tips/11638841.html

- ^ Jewish War 2.259–263

- ^ Jewish Antiquities 20.169–171

- ^ Steve Mason, Josephus and Luke-Acts, Josephus and the New Attestation (Hendrickson Publishers: Peabody, Massachusetts, 1992), pp. 185–229.

- ^ Pervo, Richard, Dating Acts: betwixt the evangelists and the apologists (Polebridge Printing, 2006), p. 161-66

Farther reading [edit]

- I. Howard Marshall. Luke: Historian and Theologian. Downers Grove, Illinois: InterVarsity Press 1970.

- F.F. Bruce. The Speeches in the Acts of the Apostles. London: The Tyndale Press, 1942.

- Helmut Koester. Ancient Christian Gospels. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Trinity Printing International, 1999.

- Colin J. Hemer. The Volume of Acts in the Setting of Hellenistic History. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 1989.

- J. Wenham, "The Identification of Luke", Evangelical Quarterly 63 (1991), 3–44

External links [edit]

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Cosmic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. Run across department titled Objections confronting the actuality.

- Jewish Encyclopedia: New Testament: The Acts of the Apostles

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Historical_reliability_of_the_Acts_of_the_Apostles

0 Response to "Scholarly Review of the Date of the Acts of the Apostles"

Post a Comment